“Buddhist diplomacy combines all these elements as Buddhist sites, teachings, personalities and heritage are usable as soft power tools by international actors”

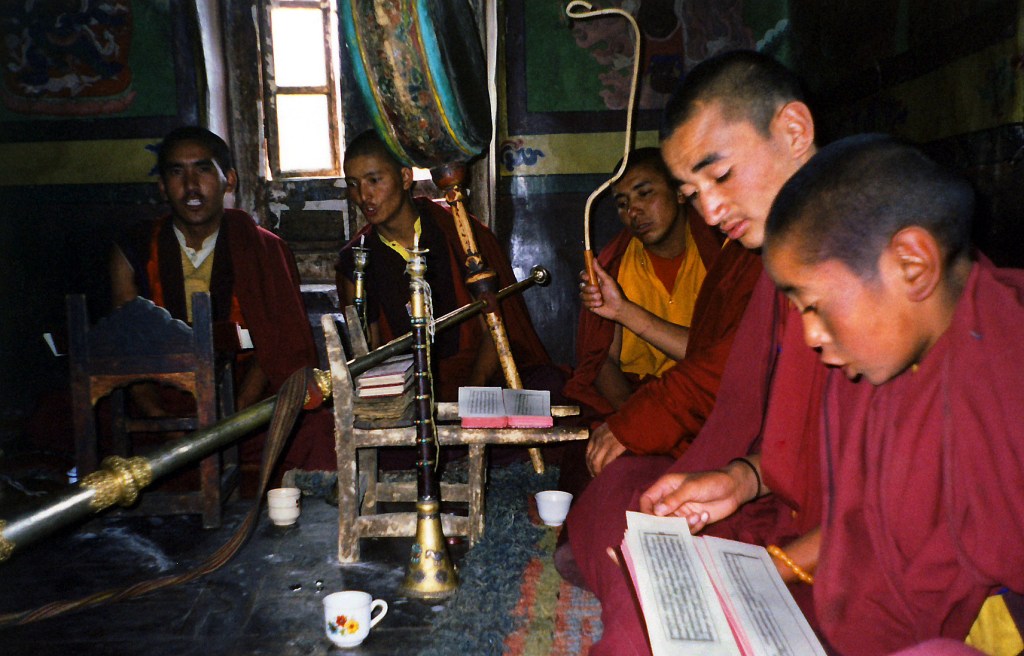

Buddhist monks at Lamayuru Monastery reading sacred texts, Ladakh, India (2000). © Dr. Ondřej Havelka (cestovatel) / Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License / Free for use / Wikimedia Commons

“Buddhism is not just a religion but an Asian identity, a spiritual connectivity with the potential of connecting different civilisations and communities along the globe” (Raj, 2022)

India and China are competing for regional dominance in Asia. China’s economic rise, strategic control of key industries and increasing influence over global markets have made it confident to position itself as a counterweight to what it sees as a Western hegemonic international order. India holds great potential as a rising power to challenge China. Being a major economy combining a youthful population, strong domestic demand and accelerating advances in technology and manufacturing. Beyond this strategic rivalry lies an often overlooked domain. Culture and religion have become central to the soft power competition between the two rivals. Both governments have rediscovered the political value of Buddhism in engaging with societies in East, Southeast and Himalayan Asia. This article will shed light on the motives and differences in the use of Buddhist diplomacy as a soft-power instrument between India and China.

Buddhism as a Soft Power Instrument

The political appeal of Buddhism rests on its philosophical ideals. The themes of Buddhism, including peace, tolerance, nonviolence and loving kindness, have universal and contemporary value and appeal. For this reason, Buddhism is uniquely suited for the projection of soft power. It historically spread without the deployment of merchants, trade routes like the silk road, missionaries and hard power, such as military strength and elite patronage. The religion conveys moral authority, cultural prestige and a sense of Asian civilisational continuity.

Soft power itself is understood as “the ability to affect others to obtain the outcomes one wants through attraction rather than coercion or payment”. Public diplomacy is defined as “government sponsored efforts aimed at communicating directly with foreign publics” that seek to convince them to support national goals. Hence, soft power is a major vehicle through which governments attempt to create this attraction. Cultural diplomacy is one subset of this. It encompasses “activities aimed at the promotion of foreign policy interests” through cultural exchange and cultural symbolism. Buddhist diplomacy combines all these elements as Buddhist sites, teachings, personalities and heritage are usable as soft power tools by international actors.

Buddhist Diplomacy within India-China Rivalry

Buddhist Diplomacy cannot be understood in a vacuum. It is embedded in a wider strategic contest for political authority and regional leadership. The Sino-Indian relationship is marked by economic competition, territorial disputes and diverging security agendas. For instance, China’s military maritime outreach in the Indian Ocean, combined with the use of debt vulnerabilities of countries such as Sri Lanka and the Maldives, has put India on alert. The rivalry extends into development policy. China’s Belt and Road Initiative has become one key flagship of its foreign policy. Yet India remains an outsider in the initiative. A core reason is that the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor goes through Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. India fears that the Belt and Road initiative will allow China to expand its geopolitical influence and gain excessive economic and diplomatic leverage over the policy choices of India’s neighbouring states.

India’s Buddhist Diplomacy within its Multi-Aligned Foreign Policy

India positions itself as the cradle of Buddhism. Although less than 1% of the country’s population (approximately 10 million) is Buddhist, it emphasises a civilisational heritage that resonates strongly across Asia. India’s foreign policy under Prime Minister Narendra Modi is treating Buddhism as a diplomatic asset and a cultural bridge to East and Southeast Asia, frequently emphasising the shared Buddhist heritage in his diplomatic speeches. Although within India and its national politics a form of “Hindu Nationalism” persists, a form of ethno-nationalist ideology that desires to make India an openly Hindu nation-state. Narendra Modi and his activities have been tied on a number of occasions to this ideology.

India’s strongest symbolic resource is its hosting of the Tibetan exile government since 1959. This has allowed India to project itself internationally as a protector of the Tibetans and a preserver of Tibetan culture and identity. The presence of the Dalai Lama has simultaneously revived Buddhism within India and enhanced its soft power credentials. This is also the most contentious issue in Sino-Indian relations, since Beijing considers the Dalai Lama a potential threat to national unity because of the fear of Tibetan separatism. New Delhi continues to invest in large-scale Buddhist conferences and global forums, including the first-ever Global Buddhist Summit in 2023 or the 2025 First Asian Buddhist Summit. These venues enable India to present itself as a peaceful connector of Asian societies. India’s Buddhist diplomacy is therefore used to consolidate regional influence by building trust.

China’s Use of Buddhist Diplomacy to Secure Regime Continuity

While India looks outward, China’s strategy is more domestically targeted. The Chinese Communist Party’s overriding objective is regime stability and continuity. Buddhism plays a significant role in this context because it has shaped Chinese civilisation for centuries. Although being an atheist state, this is crucial, as China is home to the world’s largest Buddhist population with up to 250 million practitioners. Promoting Buddhism abroad, therefore, reinforces the CCP’s narrative of a harmonious society and appeals to Buddhist constituencies within China, which are, in turn, less likely to create domestic unrest. Beijing, hence, understands Buddhism through the lens of domestic security. Tibetan Buddhism remains politically sensitive. During the Cultural Revolution, Tibetan monasteries experienced systematic repression.

Today, fears of separatism persist, from Hong Kong to Tibet and other places. This is why Beijing has invested heavily in influencing the eventual succession of the Dalai Lama. China has already convened a committee composed of government-selected Tibetan monks and key Communist Party officials to oversee the process. Controlling the next Dalai Lama would strengthen the CCP’s influence on Tibet. The Dalai Lama, however, has recently reaffirmed his plans for a successor. The Dalai Lama said that the Gaden Phodrang Trust, which manages his affairs, would oversee the search for his reincarnation. “No one else has any such authority to interfere in this matter,” he said. In direct response, Gama Cedain (a senior official of the Chinese Communist Party committee in Tibet) declared: “The central government has the indisputable final say in the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama.” The process must follow “strict religious rituals and historical conventions,” including a China-based search and approval from the central government. On top of that, China also mirrors India by organising its own Buddhist forums, such as the World Buddhist Forum. The country influences international Buddhist organisations, including the World Buddhist Sangha Council and the World Fellowship of Buddhists.

To avoid worries in Tibet, the CCP has also employed Buddhist diplomacy in Nepal. Nearly 20,000 Tibetans live there. Nepal has historically balanced Indian and Chinese domestic influence, but has more recently leaned towards China. Beijing worries that hostile forces might use Nepal (and especially the former Tibetan Kingdom of Mustang), as a platform to trigger unrest in Tibet. To increase leverage, China has linked Buddhist symbolism to development finance. For instance, it has invested heavily in Lumbini, the birthplace of the Buddha, by offering Nepal three billion dollars in BRI-supported development projects. Expanding Chinese tourism and infrastructure in Lumbini strengthens Beijing’s influence and helps ensure that Nepalese Buddhists do not become a centre of Tibetan mobilisation.

The Strategic Instrumentalisation of Buddhist Diplomacy

Both India and China use Buddhist diplomacy as a soft power tool. They do so for different strategic reasons. India utilises Buddhism to further cultural and civilisational ties with the region, even if in national politics a different narrative may persist. It hosts the Tibetan exile government and promotes international Buddhist cooperation as part of its multi-aligned foreign policy narrative. China uses Buddhism diplomacy to consolidate influence at home and to project power abroad. Its approach is primarily shaped by domestic imperatives, including regime continuity and the deeper integration of Tibet as part of the country. As this Sino-Indian competition continues to evolve, Buddhist diplomacy will remain a significant factor shaping regional alignments and strategic narratives. To control Buddhism, it will certainly matter who determines the next 15th Dalai Lama.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of Neo Institute Europa. The Neo Institute publishes contributions to foster informed public debate. While articles may be reviewed and edited, the author(s) remain solely responsible for the claims, interpretations and conclusions expressed. This content is provided for informational purposes. The Neo Institute Europa shall not be liable for any loss or damage arising from reliance on this article.